Fiction: The Bear and the Black Dog

“If the bear comes don’t run… Here take this.”

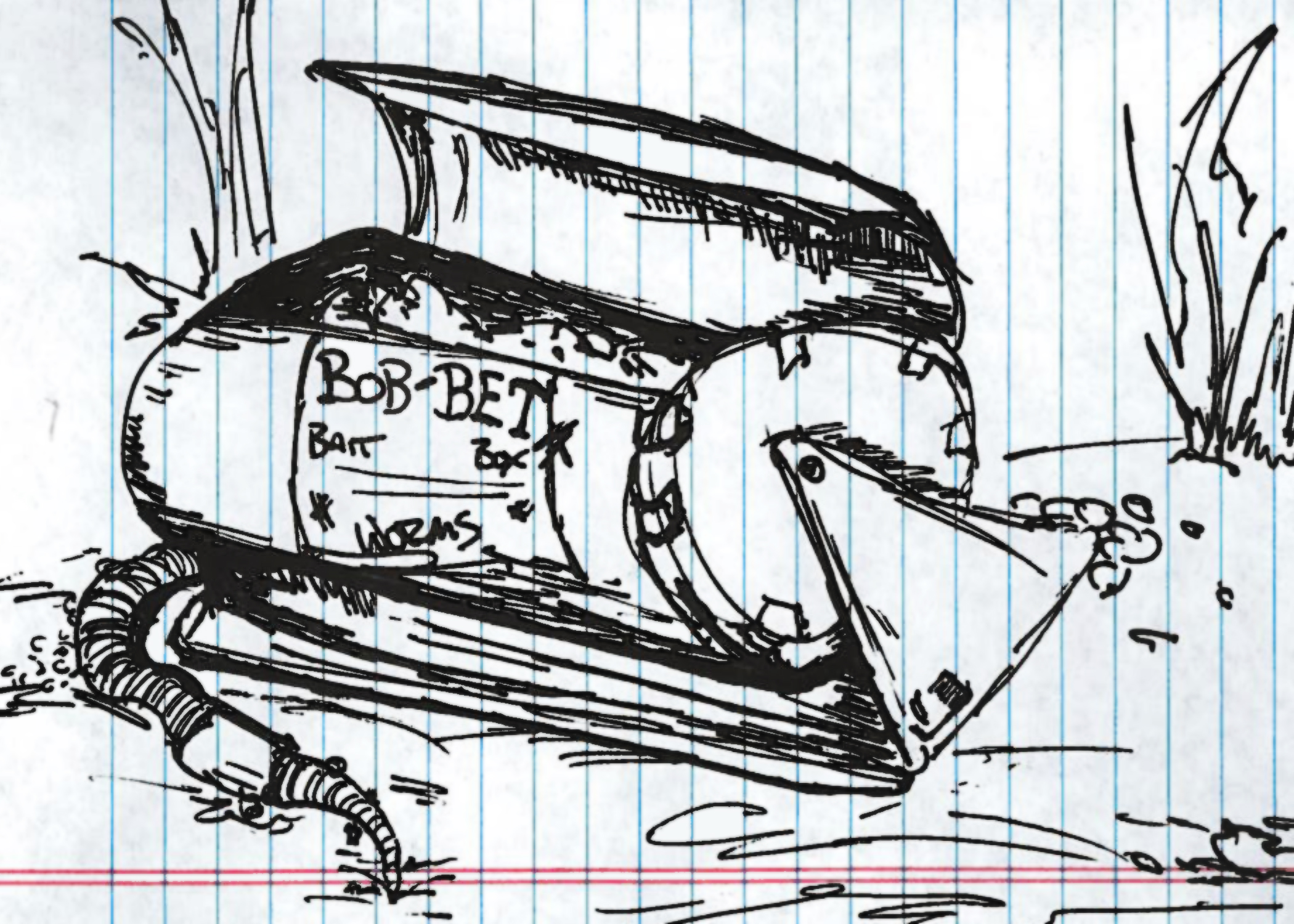

The old man handed the boy his reel and rummaged in the truck bed for the bottle of cheap schnapps. He instead found a rusted Bob-Bet can and handed it to the boy.

“Now there’s five worms in there. It should be enough for the morning but don’t go casting into the goddamned bushes. If you need more just divide them like I showed you. Alright here’s your creel.”

The creel rattled.

“Wait.”

The old man stuck his hand in it and found the schnapps, he took it and put it in his pocket.

“That’s not gonna do you any good… Alright, now head down to the bank and get started. Remember like I told you, cast just before the eddies and you should be fine. I’m going to just be around the bend over there and you can holler of you need anything. Now you’ll have Old Maddie with you and you’re a big boy, don’t be afraid to use those gum boots and step into the river aways. The fish can smell you if you’re on the bank.”

The boy wasn’t sure how a fish could smell you better out of the water than in it, but the old man knew these things so he nodded obediently.

“Catch a few and I’ll make us trout and eggs for breakfast.”

The old man grabbed his tackle and headed off into the willows that would lead him up the bank of Big Wood River and out of site. The boy turned to walk down the gravel path toward his assigned area of the bank. Old Maddie slowly and reluctantly made her way out from under the truck where she had already made herself comfortable among the dirt and dried up river rocks.

She was a good dog, large and black with gray furs around her muzzle and belly and a certain amount of dog strength that the boy knew was there, although it had never been tested in front of him. She accepted the boy, although she was always more of the old man’s dog. She came and went from his side at her own pleasure, more haunting the boy like a black and gray specter than providing him companionship. Nevertheless there was Old Maddie with the boy, her sniffing at the morning and him looking at river, trying to focus on trout and thinking about a bear.

The boy took a few steps into the shallows of the river and set to baiting his hook. He opened the Bob-Bet can and looked at the worms wriggling in the wet dirt inside. He didn’t want to touch them. He definitely didn’t want to divide them. He had seen the old man do this with a callused thumbnail slicing the worm against his own soft palm as he held the worm out, trying his best not to feel squeamish and doing a poor job. He didn’t like it and barely tolerated putting the worm on his own hook. But here in the river he baited it obediently, rather than calling the old man back over to do it for him and possibly drawing his ire. The tip of the worm shook in his hand and writhed as he pierced it through on the hook and he couldn’t help but feel bad for it in the base of his stomach and throat. Old Maddie growled lazily and moped off to a willow bush to sleep again. She had seen this routine from the boy before.

Worm on, he did his best to scan the river for low deep eddies where the big trout liked to hide. It looked like a river. But he recognized an old stump that the old man had pointed out before and did his best to cast toward it. The line landed close enough and he was glad to have the dying worm as far away from him as possible rather than wriggling around in eyesight and asking him over and over why he had killed it on his metal hook.

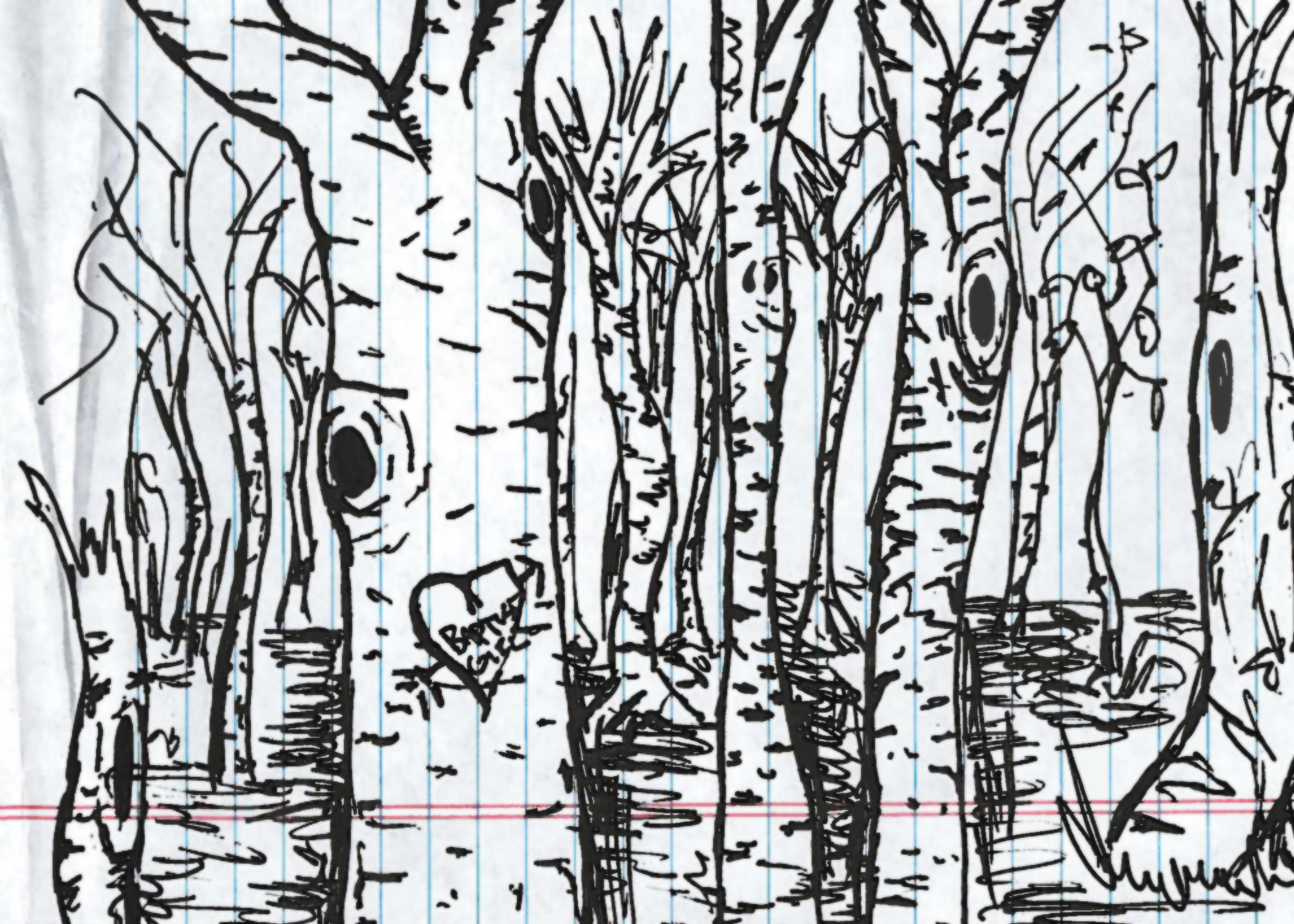

Then he stood in the river. It felt quiet. He was not yet old enough to appreciate the quiet vacancy of the Big Wood River that older men and even older boys came to crave as sanctuary. To him it just felt like a slightly dangerous boredom where nothing happened. A boredom that carried the constant feeling of being watched by the jays and nuthatches and hares and whatever else may be crawling or walking through the willows and aspens. It felt like the forest itself was the bored one and he was the jittering squirrel within it, standing in the river and waiting to be swept away by something unseen.

If the river felt dangerous the willows felt more so. Some of the older boys spent their summer afternoons among the willows in the Big Wood River marsh at the base of I-93, looking at Playboys, smoking cigarettes and trying to feel adult while sipping on warm Coors Original yellow cans they had swiped from their Uncle’s coolers—all with the protective veil of the highway separating them from disapproving mothers back in cabins and base of the Boulder Mountains keeping them safe from the wilderness at large. And all of this sounded good to the boy, if it weren’t for the willows. The things that scared him lived there—the rattlesnakes, the black bears and the suffocating tarish mud that he believed had swallowed the religious boy who disappeared from the Baptist camp two summers ago. The Baptist boy had never been found and the religious types still prayed over him and said things like “Heaven help us.” And “He’s in heaven now.” Although the boy knew better—the lost Baptist boy was in the thick liquid mud that had stolen his handmedown tennis shoe years before. Nothing was strong enough to get out of that mud, not his foot, not his shoe and not even Heaven.

The Baptists had a hot springs pool a hikeable distance from his cabin that smelled like a mixture between boiled eggs and an old liquid fart. His mother had taken him and his cousins there shortly after the Baptist boy had disappeared. While he was working his way around the egg water pool, one of the older girls from the Baptist camp was at loose ends over the missing boy and happened to latch onto him for comfort. She was more developed than the other girls and when she started crying and hugged onto him in the pool he could feel her nubby breasts against his arm and chest with only the thin layer of her swimsuit between them. She squished into him full force and noticing his excitement the girl quickly got over her grief and pinched him on the stiff wiener before giggling and swimming away. He instantly felt his heart thump from his chest down to his crotch and had to stand still in the pool for a good thirty minutes before he could safely get out.

His dallying irritated his mother– as his younger cousin’s were ready to go and had already picked out their spud candy and licorice gum from the church store. She teased him about the girl that she had barely noticed earlier and it brought the redness of shame to his shoulders and belly. But in his head on the walk back home, it still counted as one of the greatest days of his life.

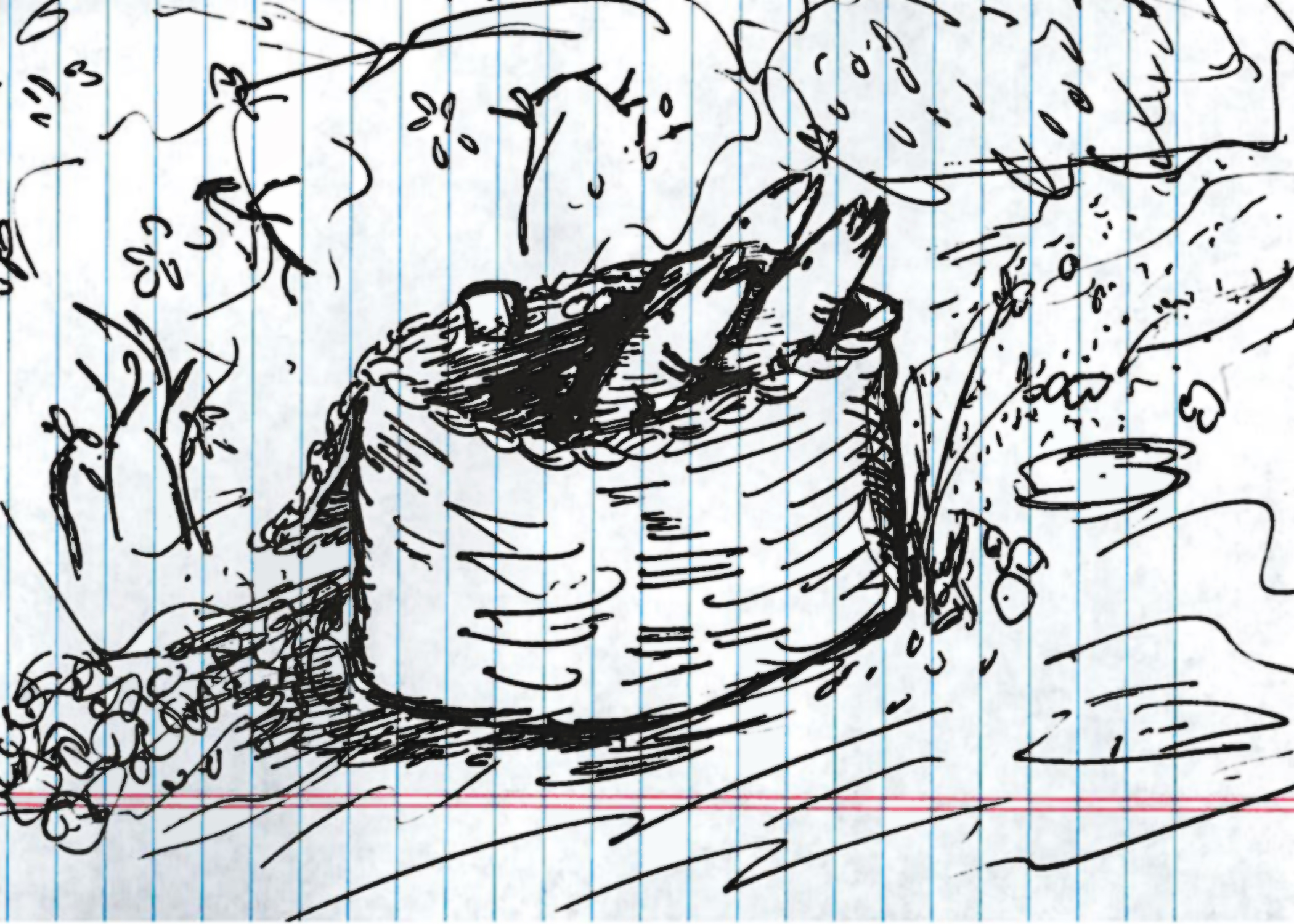

Old Maddie grumbled and turned beneath the willow where she had gotten ahold of a good green branch to chew on. She stopped chewing and belched a dog belch. It was then that the boy noticed the tug on his line and began slowly bringing it back from its resting place down the bank. The old man had shown him how to walk toward the middle of the river to change the line’s angle and not get it snagged in the roots and willow branches that hanged low over most of the river’s edge. He made his way out to the middle and brought in a respectable sized brookie with good spots and a reddish belly. He wet his hand and pulled the hook from its lip without shaking too much or feeling overly badly. He put the fish in his creel and feeling triumphant, turned toward the bank. On his second step he slipped on a loose rock and filled his boot with cold river water.

“Shit.”

It felt good to curse, even if it was still slightly awkward and only for the sake of trying it on. He made his way to the bank and put the creel in the shallowish water, weighing it down with one of the larger rocks. He sat at the bank for a minute and emptied the water from the boot as Old Maddie walked over to sniff the fish in his wicker basket, the same way she had sniffed every fish in every wicker basket since before he was catching them. He dug back into the Bob-Bet can and pulled another sad, soon to die worm from the dirt and rusted metal. He skewered it and grimaced as it writhed, before plodding out to into the middle of the river again. He cast as best he could, settling back into the same place he was before.

He glared at the willows and then squinted up toward a grove of aspens further up the mountain. The grove looked inviting, without the spikey needled ground of the pine woods that surrounded it. He thought of leaving Old Maddie to watch his gear and hiking over to the Baptist camp, finding the girl and leading her back past the river through the willows and into that grove of aspens where she might pinch his wiener again and in turn let him try a thing or two. Looking at the aspens it felt like a real possibility. And she would likely agree when she saw how nice they looked in the morning sun and understood that they could both lay on the ground softly without the dead needles poking and itching into them. He thought about sitting naked with her on a log and shooting the breeze. The fact that he had never really spoken to her, or any girl for that matter did not seem relevant. Much less the fact that he had never sat naked on a log in a wood known for carpenter ants. In his mind the grove was his, and so was the Baptist girl, to do with as he pleased. Ant bites or not.

His line jerked again. He started tried to reel it in. But having been in the aspen grove pinching various areas on the Baptist girl for the last several minutes, his mind forgot to move away from the bank and he fouled his line in the stump.

“Shit.”

It didn’t feel as good this time.

He waded over to the far side of the river soaking himself up to his thighs and giving his crotch a much different and colder sensation than the one he had been enjoying. He got to his line to realize that in addition to his rat’s nest, he still had another trout at the end of it. He was gathering it in as best he could with his hands when he heard the old man behind him.

“Lemme see.”

The boy moved out of the way as the old man gathered in the line quickly and got to the trout at the end, gaping it’s mouth and wriggling side to side with trout blood coming out. The old man grabbed it bluntly and looked into the mouth.

“It gutted the goddamned thing.”

He pulled his pliers from his pocket and jammed them into the fishes mouth. The boy had seen this before and it was disquieting. He was now brought fully away from the Baptist girl with her wandering hands and their imaginary naked log time and onto the river bank with the old man and his dying fish. The old man dug deep in the fishes belly searching for the hook with the pliers as more fish blood and what had to be some intestine came out of the mouth along with a loud metal on bone crunching noise and his own rasping grunt.

“Stupid goddamned planter fish always take it in the gut.”

The old man pulled the hook free with a smallish piece of either worm or trout insides still attached to it and handed the fish to the boy. The boy took it and smelling the man’s metallic peppermint breath, busied himself trying not to turn white or get shocky for fear of shaming the old man. Once when he was younger he cried the first time he gutted a fish in the cabin’s white enameled sink and the old man had told him not to “act like a queer.” He didn’t want to act like a queer this morning at the river and tried to keep his composure. The old man gathered the rest of the tangled line.

“Take it over to the creel, buddy. We’ll get you set back up.”

The boy walked across the river, slipping on a few rocks as the Old Man followed him. The old man had left his tackle box at the bank and grunted when he sat down next to it. He put the tangled, wrecked bits of line and hook in the bottom of it and restrung the boys hook for him. Finished, and still not thinking to wash his hands of trout death, he took out a hard salami and cheese sandwich from his shirt pocket and gave half of it to the boy.

“Here. Yellow mustard too.”

They sat eating the half sandwich on the bank in silence. Hard salami, cheddar and yellow mustard was always unusually good early in the morning. It was the old man’s specialty and it felt like cheating and getting lunch before you were supposed to even have breakfast. It may have been the only sandwich the old man knew how to make, which in itself was rewarding. The old man pulled out a Good and Value filter cigarette from his shirt pocket and took another bit of schnapps from the pint bottle. He noticed the boy looking up at him from the sandwich. He lit up the smoke and addressed him.

“Sometimes a man needs to steady his hand when he’s getting breakfast for his family… You’ll understand that when you’re older.”

It seemed to make sense and the boy nodded. Old Maddie came over and ate the last bit of the old man’s sandwich, which she truly enjoyed and he didn’t seem to mind.

“I gotta couple fish over on the other bend and I’m gonna go get’m. Gather your gear here and I’ll be back. Then we can bring some breakfast to the girls.”

The old man rose from the bank and headed back into the willows toward his bend in the river. The boy licked the salami pieces from between his teeth and went to picking his things up. Leaning for his creel he smelled the river and the fresh feeling breakfast smell of his caught fish. But then there was also a new and ancient smell of something more massive, and wet and of the deep forest more dangerous than the willows. He stood to see the bear.

It stood on its fours looking at him, its eyes feeling bored and sleepily aware of its own deadliness. Old Maddie emerged from the willow and salami sandwich to silently growl at it with the visceral old fury that was still natural to a black dog whose grandfather’s fathers had been used to battle nature back when the boy’s grandfather’s fathers needed dogs like her to do things like that. The bear addressed the dog with more of a quiet disgust than a snort. Flies crawled near its snout and the thickish scarred fur, looking like they were still trying to get at the death the bears jaws had always been a part of.

In the bear’s presence time felt like slowed to the boy, like the whole forest had stopped in its place to see him die. That the clouds had stopped their place in the sky and the aspen leaves had momentarily stopped quaking to look down upon him and the bear and him looking at it and it looking at him. And him feeling a profound nakedness, one more visceral than the feeling of dallying in front of the bathroom mirror. But a nakedness born from the bear with its fur and its claws and teeth and depth of bear knowledge that stared through him and his clothing like it stared through the collar on the black dog that needed it to say that it knew where it lived. The bear knew where it lived without question or collar, and because of that knew things the boy never could. The leaves still sat motionless as the bear pondered the shoe it once found in the black mud and all that it knew of what lay beneath it. For his turn the boy saw within the bear the blackness that even the older boys wouldn’t navigate and the late night air behind the simple cabin’s outhouse that he was forced into on nights when he could no longer wait till morning to relieve himself and so had to venture out into that blackness of night in the forest and all the millions sets of eyes on him peering from behind woodpiles and in branches and from burrows. The bear guffawed, wondering why the boy sat there, nose whistling, dog silently growling, fish waiting in a whicker basket instead of making a fine meal. The boy felt his heart thump again, stronger, more fearful and thumpish than even when Baptist girl had brought that same heart to his crotch. He stood rail still, smelling bear smell and breathing bear knowledge that he knew he was not supposed to breath.

They stood there: dog growling, boy looking, bear bored. The bear lowered its head and swayed a bit from side to side, almost deciding what to do or listening to a type of nature music that only it could here. It pawed at a few of the loose rocks along the bank before stooping and settling on the fish that had gutted the line and that the boy had left on the bank and not in his creel.

The bear in all its inherent ferocity, lowered, grabbed the fish and looked the boy once again in the eyes. Its bear brain telling him, “This is my breakfast. I am taking it because I am a bear and this is my woods and my river. I move of its rapids and I bathe of its eddies. This is my forest and my blood is of it and meant to be nursed by it. I am nursed by this trout as you were nursed by your non-bear mother. And its blood is my milk and its gills are my lungs. I know of this bank and these willows and black mud and I will always know of it. I allow you to be here as I wake of this morning and sleep of this dusk. I enter this river and leave of it as you never can. I am of it as I am of you and you are of me. I taste of it and smell of it and I am taking this trout because I am a bear and you are a boy and I am of this fish and it is mine. I am a bear and it will always be mine.”

The bear turned with the fish and headed back through the willows to its secret deep woods place to eat the trout in privacy of the boy interloper who had accidentally caught it for him. Old Maddie stopped her silent growl and went back to sniffing the remaining fish in the creel and the boy knelt to grab his pole with the fresh new line on it. The old man called from above by the truck.

“You good, boy?”

The boy grabbed the creel away from the sniffing back dog and headed back to the truck.

“You good?”

The old man repeated.

“Yes.”

“Alright, put your creel in the cooler and let’s go over to Silver Creek and find some morels for your mother, she’d like that. You wanna ride in the back with Old Maddie?”

The boy nodded and climbed in, smelling the morning nature blend with the old truck’s engine and the lingering bear smell in his nostrils and the feeling of comfort of the black dog and corrugated truck bed as he looked back at the willows and the secret impenetrable place the bear had come from as the truck disappeared onto the highway.